The Story Behind Hip Hop Culture: What Most People Don’t Know

DJ Kool Herc and Cindy Campbell’s party in the Bronx, New York City, in August 1973 sparked the birth of hip hop culture. This single event became the genre’s defining moment. The movement started locally but hip hop has now become the world’s favorite youth culture that reaches almost every country globally.

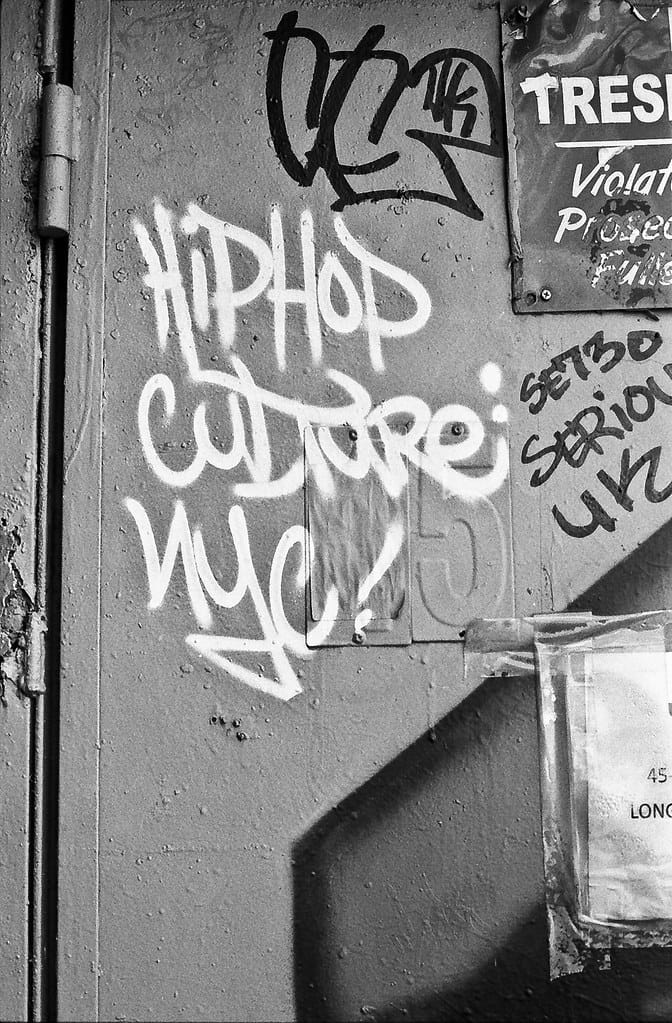

The culture began with four key elements: DJing, MCing (rapping), graffiti art, and breaking (breakdancing). These foundations have now revolutionized into a multibillion-dollar global phenomenon. The powerful forces behind hip hop culture shaped its expansion from neighborhood block parties to worldwide influence, revealing surprising details about its roots and hidden pioneers.

The Forgotten Roots: Before Hip Hop Culture Began

The birth of hip-hop at that famous Bronx party in 1973 didn’t happen by chance. Social, economic, and cultural forces came together to set the stage for this cultural revolution. The story goes back much further than most people know, spanning continents and generations.

The socioeconomic backdrop of 1970s South Bronx

The South Bronx of the 1970s looked more like a battlefield than a neighborhood. Communities fell apart as factories closed down and poor urban planning took its toll. The area became the epicenter of both economic struggle and creative resilience.

The United States faced consecutive recessions during this time. Inflation soared above 13%. New York City almost went bankrupt and made severe budget cuts that hit low-income communities the hardest.

The South Bronx started declining years before with “white flight.” Middle-class white residents moved to the suburbs in masses during the 1950s and 1960s. Black Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Caribbean immigrants became the main residents of these neighborhoods.

Robert Moses’s Cross-Bronx Expressway project dealt another blow to the community. The construction forced more than 1,500 families to leave their homes in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The highway also caused asthma rates to rise three times higher than the national average.

The situation got worse in 1972. Landlords started burning down entire neighborhoods. They realized insurance money would bring more profit than collecting rent in the failing economy. Empty lots, boarded-up windows, and burned buildings became the backdrop for artistic innovation.

Young people responded to these challenges by creating new forms of expression that mixed music, dance, visual art, and fashion. One observer put it this way: “Hip-hop came from…sadness. It came from trying to find a way to exorcize these societal demons”.

Jamaican sound system influence

Jamaica played a vital role in shaping hip-hop culture through its “sound system” tradition. This practice started in Kingston during the 1940s. DJs would pack trucks with generators, turntables, and huge speakers to throw street parties.

DJ Kool Herc brought this Jamaican tradition straight to the Bronx. Born as Clive Campbell in Kingston, he moved to New York at 12. He carried memories of dancehall parties and the “toasting” style of Jamaican DJs. Though too young to get into the parties back home, he soaked up the culture by listening from outside.

Herc became famous in New York for his powerful sound system. He emphasized heavy bass—a direct import from Jamaica. He also adapted the Jamaican “dub” technique by extending percussion breaks to keep people dancing longer.

Researcher Julian Henriques called the sound system “one of the most efficient musical distribution mechanisms”. It created what he termed “sonic dominance”—”an enveloping, immersive, and intense experience”. This approach revolutionized music distribution when mainstream radio ignored people’s music.

Connection to African oral traditions

Hip-hop’s roots stretch back to West Africa, where “griots” have told stories since the 13th century. These talented storytellers, poets, musicians, and praise singers moved through empires. They recited histories with rhythm and repetition. Many experts now see this oral tradition as rap’s earliest form.

Nigerian entrepreneur Obi Asika explained it well: “Rap is fundamentally based on vocal styling, based on call-and-response, which is the foundation of all Black music”. This call-and-response pattern—voices or instruments answering each other—runs through African music and became essential to hip-hop.

The Last Poets showed Africa’s influence on Western hip-hop culture back in 1968. They gathered in Harlem’s Mount Morris Park on Malcolm X’s birthday. Their poems mixed African-inspired call-and-response with rhythmic chanting [21, 22].

Afrika Bambaataa now calls rappers “postmodern griots”. They keep the ancient practice of preserving culture through rhythmic storytelling alive. Asika states it clearly: “All Black music, including hip-hop, comes from us [Africans]”.

Hip-hop’s building blocks traveled from African griots to Jamaican sound systems to South Bronx block parties. This journey created an array of cultural elements that sparked a worldwide movement.

“Hip hop isn’t just music—it’s the raw, unfiltered voice of generations telling their truth. From concrete jungles to global stages, it transforms struggle into poetry, pain into power, and history into rhythm. In these beats and rhymes, we find both refuge and revolution.”

The Birth of Hip Hop: Beyond DJ Kool Herc’s Party

DJ Kool Herc often gets the spotlight in hip hop stories, but the whole story shows that hip hop culture came from many people working together. That famous August 1973 party tells just part of the tale. Many hidden pioneers helped shape this cultural revolution.

The untold story of Cindy Campbell

Hip hop’s real architect wasn’t DJ Kool Herc but his sister, Cindy Campbell. This 15-year old girl hosted the now-legendary “Back-to-School Jam” with a simple dream: she wanted to buy cool clothes for school.

“You want to go back to school with something nice, different, and fresh — and you’re the only one that had it,” Campbell said about what drove her. She planned everything down to the last detail and rented the recreation room at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue for $25. Her smart business sense showed in her prices: girls paid 25 cents, boys paid 50 cents.

Campbell wrote flyers and notecards by hand to spread the word about her party. “I promoted the whole thing, I got the cards, I put Herc’s name on there; he was just interested in playing his music,” she remembered. Her parents helped too, keeping watch in the lobby.

The Campbell siblings made $300 from the jam that night – a party that would change music forever. This made Cindy the first hip hop promoter ever, though many people don’t know this part of the story.

Early block parties and their community significance

After this original party’s success, hip hop gatherings moved from indoor spaces to the streets. By next summer, DJ Kool Herc was playing free block parties all over the neighborhood.

These street parties did more than just entertain people. Tony Tone from the Cold Crush Brothers put it best: “Hip hop saved a lot of lives”. Kids in violent neighborhoods found safe spaces where “instead of getting into trouble on the streets, teens now had a place to expend their pent-up energy”.

The Smithsonian’s associate director for curatorial affairs, Dwandalyn Reece, explained that Black neighborhoods started block parties “as a tool to bring people together”. This sense of unity became hip hop’s foundation.

These outdoor events worked like open-air music schools. New DJs learned their craft and shared fresh music. Unlike downtown Manhattan’s exclusive clubs that kept Bronx kids out, these parties welcomed everyone, from kids to grandparents.

The first hip hop venues you’ve never heard of

People know 1520 Sedgwick Avenue as “the birthplace of hip-hop”, but other spots played just as big a role in shaping the culture.

Pioneer Green Eyed Genie called the Bronxdale housing projects the “Roman Empire” of its time. Disco King Mario lived there and threw legendary jams with his Chuck Chuck City crew that brought everyone together: “When I was a kid and Disco King Mario brought his equipment out and DJ’d in the Bronxdale projects, everybody would come together, cook their food, drink their beer, listen to the music, and dance with the girls”.

The West Bronx’s Concourse Plaza Hotel became another key spot. During “Plaza Tunnel nights,” DJ John Brown played tracks like “Soul Power” while the Black Spades owned the dance floor. These high-energy parties set the bar for other promoters, including Herc.

Hip hop stayed true to its roots in community centers before hitting mainstream success. DJs like Eddie Cheever and DJ Hollywood ruled the club scene back then. Public Enemy’s Chuck D said it straight: “The whole key was to get into the clubs”.

Early hip hop’s magic didn’t come from just one party or place. It lived in all these community spaces where young people turned what little they had into art that changed everything.

The Hidden Fifth Element of Hip Hop Culture

The four well-known elements of hip hop culture have a powerful but often overlooked fifth component: knowledge. Breakdancing, DJing, MCing, and graffiti showcase hip hop’s artistic side, while knowledge provides the philosophical foundation that unites and gives meaning to these elements.

Knowledge of self as hip hop’s philosophical core

“Knowledge of self” stands as an ethical pursuit to understand one’s connection to the world and create positive change. Black Islamic traditions shaped this concept, which became central to hip hop’s identity. People often describe it as hip hop’s “fifth element,” giving intellectual strength to the culture’s artistic expressions.

Islamic literature from almost a millennium ago contains the roots of “knowledge of self.” The respected 12th-century Islamic scholar Abu Hamid Al-Ghazali named the first chapter of his famous text “The Alchemy of Happiness” as “The Knowledge of Self.” This philosophical concept found its way into hip hop through artists like KRS-One, who stressed that “once you know where you come from you then know what to learn.”

Hip hop’s golden age (mid-1980s through mid-1990s) saw rappers consistently proclaim their knowledge of self in their music. Rakim’s lyrics about self-knowledge drew from Black Islamic philosophy, showing how this idea became vital to hip hop consciousness.

Afrika Bambaataa and the Zulu Nation’s principles

Afrika Bambaataa, one of hip hop’s godfathers, deserves credit for elevating knowledge to its essential role in hip hop culture. His background as a former gang member turned peacemaker gave him street credibility and intellectual vision. Bambaataa explained his mission: “I’m trying to get everybody on the fifth element — knowledge.”

Bambaataa founded the Universal Zulu Nation in the late 1970s to promote hip hop values. The organization’s motto—”Peace, Love, Unity, and Having Fun”—helped eliminate gang tensions at community events. Zulu Nation’s “Infinity Lessons” created codes of conduct for an honorable hip hop life that emphasized:

- Community service and solidarity

- Peace, wisdom, freedom, and justice

- Love, unity, and respect for both self and others

The Zulu Nation represents “knowledge, wisdom, understanding, freedom, justice, equality, peace, unity, love, respect, work, fun, overcoming the negative to the positive, economics, mathematics, science, life, truth, facts, faith, and the oneness of god.”

How knowledge shaped hip hop’s development

Knowledge turned hip hop from entertainment into a consciousness movement. This created a unique aspiration in contemporary popular music to apply philosophical principles on the ground rather than just perform them.

This consciousness sparked various forms of hip hop-based activism. Chicago’s Kuumba Lynx and Inner-City Muslim Action Network use hip hop as arts-based activism for youth development. Young people express themselves while learning about broader social contexts through this approach.

Knowledge acts as the binding force between hip hop’s artistic elements and creates context. One commentator noted that without knowledge, “a person who can rap will never be an emcee.” This explains the difference between mainstream society and the hip hop community, helping artists embrace their identity and express themselves authentically.

The Universal Zulu Nation now has chapters in dozens of countries. These chapters drive many community initiatives, including the declaration of November as Hip Hop History Month—evidence of knowledge’s lasting impact on hip hop culture’s global rise.

“Hip hop is democracy in its purest form—where language becomes currency, where innovation is born from necessity, and where anyone with truth to tell can grab the mic and change the world. It’s not just what we listen to; it’s how we breathe, move, and reimagine what’s possible.”

Women Pioneers Who Shaped Hip Hop History

Women’s untold story in hip hop shows a legacy that changed culture through innovation and determination. Their contributions shaped every part of the movement, even though mainstream stories often pushed them aside. From day one, women played key roles in hip hop through breaking, MCing, and behind-the-scenes work.

The b-girls who revolutionized breaking

B-girls have been part of hip hop from its earliest days. They faced huge challenges in a scene dominated by men. Groups like the Lady Rockers, Female Break Force, and Mercedes Ladies made their mark during hip hop’s early years. These pioneers rarely get the recognition they deserve.

Beta Langebeck’s story shows what b-girls had to deal with. She grew up in 1990s Miami and had to dress like a boy just to fit in at local breaking spots. Most times, she was the only female there. This gender gap never really went away. Sunny Choi often found herself “the only girl out of a hundred people” at breaking events.

Breaking’s physical nature created extra challenges for women. Carmarry Hall puts it simply: “It goes against our anatomy… Because our hips are our center of gravity, it’s very challenging”. All the same, women kept going. Many created special training plans to build strength for power moves.

The game changed in 2017. Japanese b-girl Ayumi Fukushima almost beat South Korea’s B-boy Kill in a battle at the Red Bull BC One World Finals. Her performance impressed everyone. Red Bull launched its first b-girl competition the next year, marking a new era for women in breaking.

Female MCs who changed the game

Female MCs fought hard to create their own identity in hip hop. MC Sha-Rock (Sharon Green) made history as “the first female rapper” with Funky 4+1. She delivered an unforgettable show on Saturday Night Live. Roxanne Shante started rap battles as a young teen in the 1980s and became famous during “The Roxanne Wars”.

MC Lyte broke new ground as the first woman to drop a full-length solo rap album with “Lyte As a Rock” in 1988. Her hit single “Ruffneck” later made her the first female rapper nominated for a Grammy.

Salt-N-Pepa (Cheryl James, Sandra Denton, and DJ Spinderella) changed everything about women in hip hop. They created their own style instead of copying the androgynous look of earlier female MCs. The group rocked bold fashion and wrote honest lyrics about sex and relationships. They made history in 1995 as the first all-women rap group to win a Grammy for “None Of Your Business”.

The mid-to-late 1990s brought new changes. Artists like Lil’ Kim and Foxy Brown challenged norms by owning their femininity and sexuality while rocking luxury fashion. Fashion designers started mixing sexy styles with high-end pieces, showing women’s growing power in hip hop’s look.

Women behind the scenes: producers and promoters

Women played crucial roles behind the turntables and in executive offices. Sylvia Robinson, Sugar Hill Records’ founder and CEO, produced the Sugarhill Gang’s 1979 hit “Rapper’s Delight.” This track helped bring hip hop into mainstream culture. She started the world’s first hip hop label and released one of the first all-female rap records, “Funk You Up” by The Sequence.

Sylvia Rhone, known as the “Godmother of the music industry,” backed many powerful female rappers during her 50-year career, including Missy Elliott and MC Lyte. She made history at Elektra as the first woman to run a Fortune 500 company-owned record label.

Women producers faced tough odds. No female has ever won a Grammy for “Producer of the Year” and only three have been nominated. Yet innovators like WondaGurl (Ebony Naomi Oshunrinde) broke through. She created a beat for Travis Scott that ended up on Jay-Z’s track “Crown” while still in high school.

Crystal Caines, a Harlem-based producer, artist, and engineer, has worked with big names like A$AP Ferg, Jack Harlow, and M.I.A. Her haunting slowed-down hip hop sound sets her apart. TRAKGIRL (Shakari Boles) not only produces for stars like Jhene Aiko and Timbaland but also supports getting more women into the male-dominated music industry.

Women in hip hop have always pushed past barriers to innovate and expand the culture. Their impact runs deep and shapes everything about hip hop today.

Underground Movements That Preserved Authentic Hip Hop

Hip hop’s commercial success in the 1990s sparked grassroots movements nationwide that aimed to keep the culture’s authentic spirit alive. Local underground communities stepped up to protect hip hop’s integrity. They created alternative spaces where artists could express themselves freely without corporate pressure.

The role of community centers in hip hop preservation

Community centers became safe havens for authentic hip hop culture in America’s urban areas. Young people learned breakdancing, DJing, graffiti, and emceeing in neighborhoods like Hunters Point and the Mission. Cleveland’s 10K Movement used these community spaces to help develop and protect hip hop through education and shows. The founder Samuel McIntosh believes hip hop “more about just bringing people together”. Today, many grassroots non-profits work together to serve nearly 30,000 Cleveland youth and families with hip hop programs.

Underground hip hop scenes across America

Hip hop scenes popped up in unexpected places beyond New York and Los Angeles. Seattle became a hub for experimental sounds and produced “some of the most unusual hip hop of any country”. The Memphis scene gave birth to influential groups like Three 6 Mafia. Their members DJ Paul and Juicy J pioneered horrorcore by releasing underground tapes as early as 1991. DJ Screw from Houston made a huge impact with his “screwed and chopped” tapes that became the foundation for future Southern hip hop. These local movements grew strong by performing in smaller markets that mainstream artists often skipped. They built loyal fans through steady releases and strong community ties.

How mixtape culture kept hip hop alive

Mixtapes became hip hop’s heartbeat—a grassroots network that spread through barbershops and car trunks. These cassettes gave new artists vital exposure in the 1970s and 1980s when record labels ignored rap music. DJ Drama explained that mixtapes let artists be creative because “you didn’t have to worry about clearances and splits and royalties”. They soon became symbols of authenticity as hip hop grew more commercial. DJ Drama later said, “Everything in hip-hop from ’95 to 2007 came from mixtapes”. Mixtape culture thrived because it was accessible and gave a platform to artists who couldn’t get mainstream attention.

Hip Hop’s Survival Through Censorship and Moral Panics

During its rise, hip hop culture faced many attempts at suppression. Moral panic campaigns and legal challenges threatened its existence. The culture not only survived but thrived, and turned censorship into a catalyst for artistic innovation.

The PMRC and attempts to silence rap music

The Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC) launched a campaign against “porn rock” in 1985. Founded by several prominent Washington wives including Tipper Gore, the group targeted rap music. The PMRC created the infamous “Filthy Fifteen” list of objectionable songs and pushed for warning labels on albums with explicit content. By August 1985, 19 record companies agreed to put “Parental Advisory” labels on certain releases.

The PMRC created their own rating system with markers for profanity (X), occult references (O), drugs/alcohol (D/A), and violence (V). The group claimed they weren’t seeking censorship, but major retailers like Walmart refused to stock labeled albums, which limited artists’ commercial reach.

How hip hop responded to mainstream criticism

Hip hop’s community responded with power and conviction. Ice-T challenged the PMRC in his track “Freedom of Speech,” stating: “The sticker on the record is what makes ’em sell gold./Can’t you see, you alcoholic idiots/The more you try to suppress us, the larger we get”. Artists like NOFX, Danzig, and Eminem released songs that criticized these censorship attempts.

Public Enemy’s Chuck D highlighted hip hop’s defiance in “Fight the Power.” The genre refused to be silenced, even when the Grammys wouldn’t televise rap award presentations in 1989. By 1990, a rap album held the record for most weeks at No. 1 on the Billboard charts, which showed the genre’s growing influence.

Legal battles that shaped hip hop expression

A troubling pattern has emerged as prosecutors use rap lyrics as evidence in criminal trials. This practice affects Black artists disproportionately. Researchers have found nearly 700 cases since the late 1980s where courts used rap lyrics as evidence.

We have a long way to go, but we can build on this progress with California’s 2022 Decriminalizing Artistic Expression Act. This law limits the use of creative works against their creators in court. The legislation shows hip hop’s ongoing fight against systemic biases while confirming its place as a legitimate art form.

Conclusion

Hip hop shows evidence of human creativity rising from hardship. This cultural force started with block parties in the Bronx and grew into a global phenomenon. It now shapes music, fashion, art, and social movements across the world.

Hip hop’s authentic spirit stays strong even after many attempts to suppress and censor it. The culture draws strength from its deep roots – African oral traditions and Jamaican sound systems. Knowledge serves as the philosophical foundation that makes it powerful.

Cindy Campbell, MC Sha-Rock, and Sylvia Robinson left their mark on every part of hip hop, but their stories stayed hidden for too long. Local underground movements and community centers became the true guardians of hip hop culture. They protected its real essence beyond profit-driven interests.

Hip hop means much more than just music – it represents resistance, strength, and cultural preservation. This amazing experience from the burned-out buildings of the South Bronx to worldwide influence shows that real artistic expression can exceed any barrier. Creative spirit and determination continue to drive lasting change.

Street wisdom meets raw talent. Let these beats be your backbone through the grind — then make noise about what moved you.

FAQs

Q1. What are the five elements of hip hop culture? The five elements of hip hop culture are DJing, MCing (rapping), graffiti art, breaking (breakdancing), and knowledge. While the first four are widely recognized artistic expressions, knowledge serves as the philosophical foundation that unites and gives meaning to all other elements.

Q2. Who was Cindy Campbell and what was her role in hip hop’s birth? Cindy Campbell was DJ Kool Herc’s sister and the true architect behind hip hop’s birth. At 15 years old, she organized the legendary “Back-to-School Jam” in August 1973, which is considered the founding event of hip hop culture. Campbell handled all the planning, promotion, and business aspects of the party.

Q3. How did mixtape culture contribute to hip hop’s development? Mixtapes were crucial to hip hop’s growth, serving as a grassroots distribution network for emerging artists in the 1970s and 1980s. They provided exposure when record labels showed little interest in rap music and offered creative freedom to artists. Mixtapes became markers of authenticity in an increasingly commercial landscape.

Q4. What role did women play in shaping hip hop history? Women have been integral to hip hop culture since its inception, making significant contributions as b-girls, MCs, producers, and promoters. Pioneers like MC Sha-Rock, Salt-N-Pepa, and Sylvia Robinson helped shape the genre’s evolution, despite often being overlooked in mainstream narratives.

Q5. How did hip hop respond to censorship attempts? When faced with censorship attempts like the PMRC’s campaign, hip hop artists responded defiantly through their music. They created songs criticizing censorship, used warning labels as badges of honor, and continued to push boundaries. This resistance helped hip hop not only survive but thrive, turning attempts at suppression into fuel for artistic innovation.

No Comments